Methaqualone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛθəˈkweɪloʊn/ |

| Trade names | Bon-Sonnil, Dormogen, Dormutil, Mequin, Mozambin, Pro Dorm, Quaalude, Somnotropon, Torinal, Tuazolona Methaqualone hydrochloride: Cateudyl, Dormir, Hyptor, Melsed, Melsedin, Mequelon, Methasedil, Nobadorm, Normorest, Noxybel, Optimil, Optinoxan, Pallidan, Parest, Parmilene, Pexaqualone, Renoval, Riporest, Sedalone, Somberol, Somnifac, Somnium, Sopor, Sovelin, Soverin, Sovinal, Toquilone, Toraflon, Tualone, Tuazol |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 70–80% |

| Elimination half-life | Biphasic (10–40; 20–60 hours) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.710 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H14N2O |

| Molar mass | 250.301 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 113 °C (235 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Methaqualone is a hypnotic sedative. It was sold under the brand names Quaalude (/ˈkweɪluːd/ KWAY-lood) and Sopor among others, which contained 300 mg of methaqualone, and sold as a combination drug under the brand name Mandrax, which contained 250 mg methaqualone and 25 mg diphenhydramine within the same tablet, mostly in Europe. Commercial production of methaqualone was halted in the mid-1980s due to widespread abuse and addictiveness. It is a member of the quinazolinone class.

Medical use

[edit]The sedative–hypnotic activity of methaqualone was recognized in 1955. Its use peaked in the early 1970s for the treatment of insomnia, and as a sedative and muscle relaxant.

Methaqualone was not recommended for use while pregnant and is in pregnancy category D.[2]

Similar to other GABAergic agents, methaqualone will produce tolerance and physical dependence with extended periods of use.[3]

Overdose

[edit]An overdose of methaqualone can lead to coma and death.[4] Additional effects are delirium, convulsions, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, vomiting, kidney failure, and death through cardiac or respiratory arrest. Methaqualone overdose resembles barbiturate poisoning, but with increased motor difficulties and a lower incidence of cardiac or respiratory depression. The standard single tablet adult dose of Quaalude brand of methaqualone was 300 mg when made by Lemmon. A dose of 8000 mg is lethal and a dose as little as 2000 mg could induce a coma if taken with an alcoholic beverage.[5]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Methaqualone primarily acts as a sedative, relieving anxiety and promoting sleep. Methaqualone binds to GABA-A receptors, and it shows negligible affinity for a wide array of other potential targets, including other receptors and neurotransmitter transporters.[6] Methaqualone is a positive allosteric modulator at many subtypes of GABA-A receptor, similar to classical benzodiazepines such as diazepam. GABA-A receptors are inhibitory, so methaqualone tends to inhibit action potentials, similar to GABA itself or other GABA-A agonists. Unlike most benzodiazepines, methaqualone acts as a negative allosteric modulator at a few GABA-A receptor subtypes, which tends to cause an excitatory response in neurons expressing those receptors. Because methaqualone can be either excitatory or inhibitory depending on the subunit composition of the GABA-A receptor, it can be characterized as a mixed GABA-A receptor modulator.[6] The methaqualone binding site is distinct from the benzodiazepine, barbiturate, and neurosteroid binding sites on the GABA-A receptor complex, and it may partially overlap with the etomidate binding site.[6]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Methaqualone peaks in the bloodstream within several hours, with a half-life of 20–60 hours.

History

[edit]Methaqualone was first synthesized in India in 1951 by Indra Kishore Kacker and Syed Husain Zaheer, who were conducting research on finding new antimalarial medications.[5][7][8] In 1962, methaqualone was patented in the United States by Wallace and Tiernan.[9] By 1965, it was the most commonly prescribed sedative in Britain, where it has been sold legally under the names Malsed, Malsedin, and Renoval. In 1965, a methaqualone/antihistamine combination was sold as the sedative drug Mandrax in Europe, by Roussel Laboratories (now part of Sanofi S.A.). In 1972, it was the sixth-bestselling sedative in the US,[10] where it was legal under the brand name Quaalude.

Quaalude in the United States was originally manufactured in 1965 by the pharmaceutical firm William H. Rorer, Inc., based in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. The drug name "Quaalude" is a portmanteau, combining the words "quiet interlude" and shared a stylistic reference to another drug marketed by the firm, Maalox.[11]

In 1978, Rorer sold the rights to manufacture Quaalude to the Lemmon Company of Sellersville, Pennsylvania. At that time, Rorer chairman John Eckman commented on Quaalude's bad reputation stemming from illegal manufacture and use of methaqualone, and illegal sale and use of legally prescribed Quaalude: "Quaalude accounted for less than 2% of our sales, but created 98% of our headaches."[5]

Both companies still regarded Quaalude as an excellent sleeping drug. Lemmon, well aware of Quaalude's public image problems, used advertisements in medical journals to urge physicians "not to permit the abuses of illegal users to deprive a legitimate patient of the drug". Lemmon also marketed a small quantity under another name, Mequin, so doctors could prescribe the drug without the negative connotations.[5]

The rights to Quaalude were held by the JB Roerig & Company division of Pfizer, before the drug was discontinued in the United States in 1985, mainly due to its psychological addictiveness, widespread abuse, and illegal recreational use.[12]

A 2024 Hungarian investigative documentary reported on large-scale production and sales of the drug by the Hungarian People's Republic to the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. It asserts that a Hungarian state-owned company utilized connections to Colombian drug cartels to facilitate the sale of extraordinary amounts to the United States.[13][14]

Society and culture

[edit]Methaqualone became increasingly popular as a recreational drug and club drug in the late 1960s and 1970s, known variously as "ludes" or "disco biscuits"[15] due to its widespread use during the popularity of disco in the 1970s, or "sopers" (also "soaps") in the United States and Canada, and "mandrakes" and "mandies" in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. The substance was sold both as a free base and as a salt (hydrochloride).

Brand names

[edit]It was sold under the brand name Quaalude (sometimes stylized "Quāālude" in the United States and Canada),[16] and Mandrax in the UK, South Africa, and Australia.

Regulation

[edit]Methaqualone was initially placed in Schedule I as defined by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances, but was moved to Schedule II in 1979.[17]

In Canada, methaqualone is listed in Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and requires a prescription, but it is no longer manufactured. Methaqualone is banned in India.[18]

In the United States it was withdrawn from the market in 1983 and made a Schedule I drug in 1984.[19]

Recreational

[edit]

Methaqualone became increasingly popular as a recreational drug in the late 1960s and 1970s, known variously as "ludes" or "sopers" and "soaps" (sopor is a Latin word for sleep) in the United States and "mandrakes" and "mandies" in the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

The drug was more tightly regulated in Britain under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and in the U.S. from 1973. It was withdrawn from many developed markets in the early 1980s. In the United States it was withdrawn in 1983 and made a Schedule I drug in 1984. It has a DEA ACSCN of 2565 and in 2022 the aggregate annual manufacturing quota for the United States was 60[20] grams.

Mention of its possible use in some types of cancer and AIDS treatments has periodically appeared in the literature since the late 1980s. Research does not appear to have reached an advanced stage. The DEA has also added the methaqualone analogue mecloqualone (also a result of some incomplete clandestine syntheses) to Schedule I as ACSCN 2572, with a manufacturing quota of 30 g.[20]

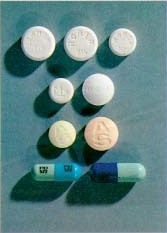

Gene Haislip, the former head of the Chemical Control Division of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), told the PBS documentary program Frontline, "We beat 'em." By working with governments and manufacturers around the world, the DEA was able to halt production and, Haislip said, "eliminated the problem".[21][22] Methaqualone was manufactured in the United States under the name Quaalude by the pharmaceutical firms Rorer and Lemmon with the numbers 714 stamped on the tablet, so people often referred to Quaalude as 714's, "Lemmons", or "Lemmon 7's".

Methaqualone was also manufactured in the US under the trade names Sopor and Parest. After the legal manufacture of the drug ended in the United States in 1982, underground laboratories in Mexico continued the illegal manufacture of methaqualone throughout the 1980s, continuing the use of the "714" stamp, until their popularity waned in the early 1990s. Drugs purported to be methaqualone are in a significant majority of cases found to be inert, or contain diphenhydramine or benzodiazepines.

Illicit methaqualone is one of the most commonly used recreational drugs in South Africa. Manufactured clandestinely, often in India, it comes in tablet form, but is smoked with marijuana. This method of ingestion is known as "white pipe".[23][24] It is popular elsewhere in Africa and in India.[24]

Chemical weapon – Project Coast

[edit]Illegal efforts to weaponize methaqualone have occurred. During the 1980s, the apartheid regime in South Africa ordered the covert manufacture of a large amount of methaqualone at the front company Delta G Scientific Company, as part of a secret chemical weapons program known as Project Coast.[25] Methaqualone was given the codename MosRefCat (Mossgas Refinery Catalyst). Details of this activity came to light during the 1998 hearings of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Sexual assault

[edit]Actor Bill Cosby admitted in a 2015 civil deposition to giving methaqualone to women before allegedly sexually assaulting them.[26][27] Film director Roman Polanski was convicted in 1977 of sexually assaulting a 13-year-old girl after giving her alcohol and methaqualone.[28]

Popular culture

[edit]Quaaludes are mentioned in the 1983 film Scarface, when Al Pacino's character Tony Montana says, "Another quaalude... she'll love me again." Quaaludes are also referenced extensively in the 2013 film The Wolf of Wall Street.[29]

Parody glam rocker "Quay Lewd", one of the costumed performance personae used by Tubes singer Fee Waybill, was named after the drug. Many songs also refer to quaaludes, including the following: David Bowie's "Time" ("Time, in quaaludes and red wine") and "Rebel Rebel" ("You got your cue line/And a handful of 'ludes"); "Cosmic Doo Doo" by the American country music singer-songwriter Blaze Foley ("Got some quaaludes in their purse"); "That Smell" by Lynyrd Skynyrd ("Can't speak a word when you're full of 'ludes"); "Flakes" by Frank Zappa ("(Wanna buy some mandies, Bob?)"); "Straight Edge" by Minor Threat ("Laugh at the thought of eating ludes"); and "Kind of Girl" by French Montana ("That high got me feelin' like the Quaaludes from Wolf of Wall Street").

Season 18 of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit addresses Quaalude administration as a date rape drug in episode 9, "Decline and Fall", which aired January 18, 2017.[30][31] In True Detective season 1, Rust Cohle's use of Quaaludes is briefly mentioned in several episodes.[32]

It is also used by Patrick Melrose in Edward St Aubyn's 1992 novel Bad News.[citation needed]

Further reading

[edit]- Hammer H, Bader BM, Ehnert C, Bundgaard C, Bunch L, Hoestgaard-Jensen K, et al. (August 2015). "A Multifaceted GABAA Receptor Modulator: Functional Properties and Mechanism of Action of the Sedative-Hypnotic and Recreational Drug Methaqualone (Quaalude)". Molecular Pharmacology. 88 (2): 401–420. doi:10.1124/mol.115.099291. PMC 4518083. PMID 26056160.

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ "Methaqualone in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding". TheDrugSafety.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Suzuki T, Koike Y, Chida Y, Misawa M (April 1988). "Cross-physical dependence of several drugs in methaqualone-dependent rats". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 46 (4): 403–410. doi:10.1254/jjp.46.403. PMID 3404770.

- ^ "Recreational drugs tranquilizers". Drug Library EU. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02.

- ^ a b c d Linder L (28 May 1981). Simons Jr DC, Mayer B, Nordyke R, Torrey A (eds.). "Quaalude manufacturer: Image hurt by street use". Lawrence Journal-World. Vol. 123, no. 148. Lawrence, Kansas, United States of America. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved 16 August 2013 – via Google Newspapers.

Eckman/Fisher

- ^ a b c Hammer H, Bader BM, Ehnert C, Bundgaard C, Bunch L, Hoestgaard-Jensen K, et al. (August 2015). "A Multifaceted GABAA Receptor Modulator: Functional Properties and Mechanism of Action of the Sedative-Hypnotic and Recreational Drug Methaqualone (Quaalude)". Molecular Pharmacology. 88 (2): 401–420. doi:10.1124/mol.115.099291. PMC 4518083. PMID 26056160.

- ^ van Zyl EF (November 2001). "A survey of reported synthesis of methaqualone and some positional and structural isomers". Forensic Science International. 122 (2–3): 142–9. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00484-4. PMID 11672968.

- ^ Kacker IK, Zaheer SH (1951). "Potential Analgesics. Part I. Synthesis of substituted 4-quinazolones". J. Ind. Chem. Soc. 28: 344–346.

- ^ U.S. patent 3,135,659

- ^ Foltz RL, Fentiman AF, Foltz RB (August 1980). "GC/MS assays for abused drugs in body fluids" (PDF). NIDA Research Monograph. 32. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Health and Human Services: 1–198. PMID 6261132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-22.

- ^ "Dividends: Dropping the Last 'Lude". Time. 28 November 1983. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ Silverstein S. "Quaaludes Again". Captain Wayne's Mad Music.com.

- ^ "A nagy titkosszolgálati drogjátszma – amikor a magyar Chinoin látta el kábítószerrel Amerikát | Válasz Online" (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- ^ Jamrik L (2024-01-08), Vörös narkó (Documentary), Imre Csók, András Dezsö, Béla Ficzere, X-Trame, retrieved 2024-09-08

- ^ Bekiempis V (August 2, 2015). "Do People Still Take Quaaludes?". Newsweek. NEWSWEEK DIGITAL LLC. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Rile K (1983). Winter Music (First ed.). Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 41, 59. ISBN 978-0-316-74657-1.

- ^ Sandouk L. "green-lists". www.incb.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ "Drugs banned in India". Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- ^ "Methaqualone". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2021-05-19.

- ^ a b Drug Enforcement Administration (2 December 2021). "Established Aggregate Production Quotas for Schedule I and II Controlled Substances and Assessment of Annual Needs for the List I Chemicals Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine for 2022". Federal Register, the Daily Register of the United States Government.

- ^ Ferns S (25 October 2007). "Lecture: Gene Haislip : The Chemical Connection: A Historical Perspective on Chemical Control" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration Museum Lecture Series. Arlington, Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2014.

- ^ Piccini S (Spring 2010). "Drug Warrior: The DEA's Gene Haislip '60, B.C.L. '63 Battled Worldwide Against the Illegal Drug Trade – and Scored a Rare Victory" (PDF). William & Mary Alumni Magazine. College of William & Mary.

- ^ "Mandrax". DrugAware. Reality Media. 2003. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ a b McCarthy G, Myers B, Siegfried N (April 2005). "Treatment for methaqualone dependence in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004146.pub2. PMID 15846700.

- ^ "Project Coast: Apartheid's Chemical and Biological Warfare Program" (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR).

- ^ Bowley G, Ember S (2015-07-19). "Bill Cosby, in Deposition, Said Drugs and Fame Helped Him Seduce Women". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Bowley G, Somaiya R (2015-07-07). "Bill Cosby Admission About Quaaludes Offers Accusers Vindication". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Freeman H (2018-01-30). "What does Hollywood's reverence for child rapist Roman Polanski tell us?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Loughrey C (18 September 2017). "Jordan Belfort had to teach Leonardo DiCaprio how to look like he was on drugs for Wolf of Wall Street". The Independent. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Janna Dela Cruz (January 15, 2017). "'Law & Order: SVU' season 18 episode 9 spoilers: Bob Gunton guest stars as billionaire rapist". The Christian Times. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Jack Ori (January 18, 2017). "Law & Order: SVU Season 18 Episode 9 Review: Decline and Fall". TV Fanatic. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ "True Detective" The Long Bright Dark (TV Episode 2014) - IMDb. Retrieved 2024-09-09 – via www.imdb.com.