Argument from poor design

| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

|

The argument from poor design, also known as the dysteleological argument, is an argument against the assumption of the existence of a creator God, based on the reasoning that any omnipotent and omnibenevolent deity or deities would not create organisms with the perceived suboptimal designs that occur in nature.

The argument is structured as a basic modus ponens: if "creation" contains many defects, then design appears an implausible theory for the origin of earthly existence. Proponents most commonly use the argument in a weaker way, however: not with the aim of disproving the existence of God, but rather as a reductio ad absurdum of the well-known argument from design (which suggests that living things appear too well-designed to have originated by chance, and so an intelligent God or gods must have deliberately created them).

Although the phrase "argument from poor design" has seen little use, this type of argument has been advanced many times using words and phrases such as "poor design", "suboptimal design", "unintelligent design" or "dysteleology/dysteleological". The nineteenth-century biologist Ernst Haeckel applied the term "dysteleology" to the implications of organs so rudimentary as to be useless to the life of an organism.[1] In his 1868 book Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (The History of Creation), Haeckel devoted most of a chapter to the argument, ending with the proposition (perhaps with tongue slightly in cheek) of "a theory of the unsuitability of parts in organisms, as a counter-hypothesis to the old popular doctrine of the suitability of parts".[1] In 2005, Donald Wise of the University of Massachusetts Amherst popularised the term "incompetent design" (a play on "intelligent design"), to describe aspects of nature seen as flawed in design.[2]

Traditional Christian theological responses generally posit that God constructed a perfect universe but that humanity's misuse of its free will to rebel against God has resulted in the corruption of divine good design.[3][4][5]

Overview

[edit]

The argument runs that:

- An omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent creator God would create organisms that have optimal design.

- Organisms have features that are suboptimal.

- Therefore, God either did not create these organisms or is not omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent.

It is sometimes used as a reductio ad absurdum of the well-known argument from design, which runs as follows:

- Living things are too well-designed to have originated by chance.

- Therefore, life must have been created by an intelligent creator.

- This creator is God.

"Poor design" is consistent with the predictions of the scientific theory of evolution by means of natural selection. This predicts that features that were evolved for certain uses are then reused or co-opted for different uses, or abandoned altogether; and that suboptimal state is due to the inability of the hereditary mechanism to eliminate the particular vestiges of the evolutionary process.

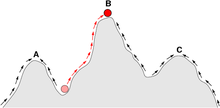

In fitness landscape terms, natural selection will always push "up the hill", but a species cannot normally get from a lower peak to a higher peak without first going through a valley.

The argument from poor design is one of the arguments that was used by Charles Darwin;[6] modern proponents have included Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Dawkins, and Nathan H. Lents. They argue that such features can be explained as a consequence of the gradual, cumulative nature of the evolutionary process. Theistic evolutionists generally reject the argument from design, but do still maintain belief in the existence of God.[citation needed]

Examples

[edit]In humans

[edit]Fatal flaws

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

American scientist Nathan H. Lents published his book on poor design in the human body and genome in 2018 titled Human Errors. The book ignited a firestorm of criticism from the creationist community[7][8] but was well received by the scientific community and received unanimously favorable reviews[9] in the dozens of non-creationist media outlets that covered it.

Several defects in human anatomy can result in death, especially without modern medical care:

- In the human female, a fertilized egg can implant into the fallopian tube, cervix or ovary rather than the uterus causing an ectopic pregnancy. The existence of a cavity between the ovary and the fallopian tube could indicate a flawed design in the female reproductive system. Prior to modern surgery, ectopic pregnancy invariably caused the deaths of both mother and baby. Even in modern times, in almost all cases the pregnancy must be aborted to save the life of the mother.

- In the human female, the birth canal passes through the pelvis. The prenatal skull will deform to a surprising extent. However, if the baby's head is significantly larger than the pelvic opening, the baby cannot be born naturally. Prior to the development of modern surgery (caesarean section), such a complication would lead to the death of the mother, the baby, or both. Other birthing complications such as breech birth are worsened by this position of the birth canal.

- In the human male, testes develop initially within the abdomen. Later during gestation, they migrate through the abdominal wall into the scrotum. This causes two weak points in the abdominal wall where hernias can later form. Prior to modern surgical techniques, complications from hernias, such as intestinal blockage and gangrene, usually resulted in death.[10]

- The existence of the pharynx, a passage used for both ingestion and respiration, with the consequent drastic increase in the risk of choking.

- The breathing reflex is stimulated not directly by the absence of oxygen but indirectly by the presence of carbon dioxide. This means that high concentrations of inert gases, such as nitrogen and helium, can cause suffocation without any biological warning.Furthermore, at high altitudes, oxygen deprivation can occur in unadapted individuals who do not consciously increase their breathing rate.

- The human appendix is a vestigial organ thought to serve no purpose. Appendicitis, an infection of this organ, is a certain death without medical intervention. "During the past few years, however, several studies have suggested its immunological importance for the development and preservation of the intestinal immune system."[11]

- Tinnitus, a phantom auditory sensation, is a maladaptation resulting from hearing loss most often caused by exposure to loud noise.[12] Tinnitus serves no practical purpose, reduces quality of life, may cause depression, and when severe can lead to suicide.[13]

Other flaws

[edit]- Barely used nerves and muscles, such as the plantaris muscle of the foot,[14] that are missing in part of the human population and are routinely harvested as spare parts if needed during operations. Another example is the muscles that move the ears, which some people can learn to control to a degree, but serve no purpose in any case.[15]

- The common malformation of the human spinal column, leading to scoliosis, sciatica and congenital misalignment of the vertebrae. The spinal cord cannot ever properly heal if it is damaged, because neurons have become so specialized that they are no longer able to regrow once they reach their mature state. The spinal cord, if broken, will never repair itself and will result in permanent paralysis.[16]

- The route of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is such that it travels from the brain to the larynx by looping around the aortic arch. This same configuration holds true for many animals; in the case of the giraffe, this results in about twenty feet of extra nerve.

- Almost all animals and plants synthesize their own vitamin C, but humans cannot because the gene for this enzyme is defective (Pseudogene ΨGULO).[17] Lack of vitamin C results in scurvy and eventually death. The gene is also non-functional in other primates and in guinea pigs, but is functional in most other animals.[18]

- The prevalence of congenital diseases and genetic disorders such as Huntington's disease.

- The male urethra passes directly through the prostate, which can produce urinary difficulties if the prostate becomes swollen.[19]

- Crowded teeth and poor sinus drainage, as human faces are significantly flatter than those of other primates although humans share the same tooth set. This results in a number of problems, most notably with wisdom teeth, which can damage neighboring teeth or cause serious infections of the mouth.[20]

- The structure of human eyes (as well as those of all vertebrates). The retina is 'inside out'. The nerves and blood vessels lie on the surface of the retina instead of behind it as is the case in many invertebrate species. This arrangement forces a number of complex adaptations and gives mammals a blind spot.[21] Having the optic nerve connected to the side of the retina that does not receive the light, as is the case in cephalopods, would avoid these problems.[22] Lents and colleagues have proposed that the tapetum lucidum, the reflective surface behind vertebrate retinas, has evolved to overcome the limitations of the inverted retina,[23] as cephalopods have never evolved this structure.[24] However, an 'inverted' retina actually improves image quality through müller cells by reducing distortion.[25] The effects of the blind spots resulting from the inverted retina are cancelled by binocular vision, as the blind spots in both eyes are oppositely angled. Additionally, as cephalopod eyes lack cone cells and might be able to judge color by bringing specific wavelengths to a focus on the retina, an inverted retina might interfere with this mechanism.[26]

- Humans are attracted to junk food's non-nutritious ingredients, and even wholly non-nutritious psychoactive drugs, and can experience physiological adaptations to prefer them to nutrients.

Other life

[edit]- In the African locust, nerve cells start in the abdomen but connect to the wing. This leads to unnecessary use of materials.[10]

- Intricate reproductive devices in orchids, apparently constructed from components commonly having different functions in other flowers.

- The use by pandas of their enlarged radial sesamoid bones in a manner similar to how other creatures use thumbs.[10]

- The existence of unnecessary wings in flightless birds, e.g. ostriches.[27]

- The enzyme RuBisCO has been described as a "notoriously inefficient" enzyme,[28] as it is inhibited by oxygen, has a very slow turnover and is not saturated at current levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The enzyme is inhibited as it is unable to distinguish between carbon dioxide and molecular oxygen, with oxygen acting as a competitive enzyme inhibitor. However, RuBisCO remains the key enzyme in carbon fixation, and plants overcome its poor activity by having massive amounts of it inside their cells, making it the most abundant protein on Earth.[29]

- Sturdy but heavy bones, suited for non-flight, occurring in animals like bats. Or, on the converse: unstable, light, hollow bones, suited for flight, occurring in birds like penguins and ostriches, which cannot fly.

- Various vestigial body parts, like the femur and pelvis in whales (evolution indicates the ancestors of whales lived on land).

- Turritopsis dohrnii and species of the genus Hydra have biological immortality, but most animals do not.

- Many species have strong instincts to behave in response to a certain stimulus. Natural selection can leave animals behaving in detrimental ways when they encounter a supernormal stimulus - like a moth flying into a flame.

- Plants are green and not black, as chlorophyll absorbs green light poorly, even though black plants would absorb more light energy.

- Whales and dolphins breathe air, but live in the water, meaning they must swim to the surface frequently to breathe.

- Albatrosses cannot take off or land properly.

Counterarguments

[edit]Specific examples

[edit]Intelligent design proponent William Dembski questions the first premise of the argument, claiming that "intelligent design" does not need to be optimal.[30]

While the appendix has been previously credited with very little function, research has shown that it serves an important role in the fetus and young adults. Endocrine cells appear in the appendix of the human fetus at around the 11th week of development, which produce various biogenic amines and peptide hormones, compounds that assist with various biological control (homeostatic) mechanisms. In young adults, the appendix has some immune functions.[31]

Responses to counterarguments

[edit]In response to the claim that uses have been found for "junk" DNA, proponents note that the fact that some non-coding DNA has a purpose does not establish that all non-coding DNA has a purpose, and that the human genome does include pseudogenes that are nonfunctional "junk", with others noting that some sections of DNA can be randomized, cut, or added to with no apparent effect on the organism in question.[32] The original study that suggested that the Makorin1-p1 served some purpose[33] has been disputed.[34] However, the original study is still frequently cited in newer studies and articles on pseudogenes previously thought to be nonfunctional.[35]

As an argument regarding God

[edit]The argument from poor design is sometimes interpreted, by the argumenter or the listener, as an argument against the existence of God, or against characteristics commonly attributed to a creator deity, such as omnipotence, omniscience, or personality. In a weaker form, it is used as an argument for the incompetence of God. The existence of "poor design" (as well as the perceived prodigious "wastefulness" of the evolutionary process) would seem to imply a "poor" designer, or a "blind" designer, or no designer at all. In Gould's words, "If God had designed a beautiful machine to reflect his wisdom and power, surely he would not have used a collection of parts generally fashioned for other purposes. Orchids are not made by an ideal engineer; they are jury-rigged...."[36]

The apparently suboptimal design of organisms has also been used by proponents of theistic evolution to argue in favour of a creator deity who uses natural selection as a mechanism of his creation.[37] Arguers from poor design regard counter-arguments as a false dilemma, imposing that either a creator deity designed life on earth well or flaws in design indicate the life is not designed. This allows proponents of intelligent design to cherry pick which aspects of life constitute design, leading to the unfalsifiability of the theory. Christian proponents of both intelligent design and creationism may claim that good design indicates the creative intelligence of their God, while poor design indicates corruption of the world as a result of free will that caused the fall of man (for example, in Genesis 3:16 Yahweh says to Eve "I will increase your trouble in pregnancy").[38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Haeckel, Ernst (1892). The History of Creation. Appleton, New York: D. Appleton. p. 331.

- ^ Wise, Donald (2005-07-22). ""Intelligent" Design versus Evolution". Science. 309 (5734). AAAS: 556–557. doi:10.1126/science.309.5734.556c. PMID 16040688. S2CID 5241402.

- ^ Harry Hahne, The Corruption and Redemption of Creation: Nature in Romans 8, Volume 34

- ^ Gregory A. Boyd, God at War: The Bible & Spiritual Conflict

- ^ ed. Charles Taliaferro, Chad Meister, The Cambridge Companion to Christian Philosophical Theology, pages 160-161 - "Fundamental to the position is Augustine's view that the universe God created is good; everything in the universe is good and has good purpose [...]. [...] How did evil arise? It came about, he maintains, through free will. [...] some of God's free creatures turned their will from God, the supreme Good, to lesser goods. [...] It happened first with the angels and then [...] with humans. This is how moral evil entered the universe and this moral fall, or sin, also brought with it tragic cosmic consequences, for it ushered in natural evil as well."

- ^ Darwin, Charles. The Origin of Species, 6th ed., Ch. 14.

- ^ "Creation: Review of Human Errors by Nathan H Lents".

- ^ "Evolution News: articles about Human Errors".

- ^ "Human Errors: The Human Evolution Blog". 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Colby, Chris; Loren Petrich (1993). "Evidence for Jury-Rigged Design in Nature". Talk.Origins. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11.

- ^ Kooij, I. A.; Sahami, S.; Meijer, S. L.; Buskens, C. J.; Te Velde, A. A. (October 2016). "The immunology of the vermiform appendix: a review of the literature". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 186 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/cei.12821. ISSN 1365-2249. PMC 5011360. PMID 27271818.

- ^ Shore, Susan (2016). "Maladaptive plasticity in tinnitus-triggers, mechanisms and treatment". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 12 (3): 150–160. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.12. PMC 4895692. PMID 26868680.

- ^ Cheng, YF (2023). "Tinnitus and risk of attempted suicide: A one year follow-up study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 322: 141–145. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.009. PMID 36372122. S2CID 253472609.

- ^ Selim, Jocelyn (June 2004). "Useless Body Parts". Discover. 25 (6). Archived from the original on 2011-08-17.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1892). The History of Creation. Appleton, New York: D. Appleton. p. 328.

- ^ "Nervous System Guide by the National Science Teachers Association." Nervous System Guide by the National Science Teachers Association. National Science Teachers Association, n.d. Web. 7 November 2013. <"Nervous System Guide by the National Science Teachers Association". Archived from the original on 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2013-11-07.>

- ^ Nishikimi M, Yagi K (December 1991). "Molecular basis for the deficiency in humans of gulonolactone oxidase, a key enzyme for ascorbic acid biosynthesis". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1203S – 1208S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1203s. PMID 1962571. S2CID 27631027.

- ^ Ohta Y, Nishikimi M (October 1999). "Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1472 (1–2): 408–11. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00123-3. PMID 10572964.

- ^ Gregory, T. Ryan (December 2009). "The Argument from Design: A Guided Tour of William Paley's Natural Theology (1802)". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2 (4): 602–611. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0184-6. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 35806252.

- ^ "Wisdom Teeth." American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS). AAOMS, n.d. Web. 7 November 2013. <"Wisdom Teeth | AAOMS.org". Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2013-11-07.>.

- ^ Nave, R. "The Retina." of the Human Eye. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 November 2013. <"The Retina of the Human Eye". Archived from the original on 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2015-06-03.>.

- ^ "Squid Brains, Eyes, and Color." Squid Brains, Eyes, and Color. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 November 2013. <"Squid Brains, Eyes, and Color". Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-07.>.

- ^ Vee, Samantha; Barclay, Gerald; Lents, Nathan H. (2022). "The glow of the night: The tapetum lucidum as a co‐adaptation for the inverted retina". BioEssays. 44 (10). doi:10.1002/bies.202200003. S2CID 251864970.

- ^ "The Night Begins to Shine: The Tapetum Lucidum and Our Backward Retinas | Skeptical Inquirer". 29 December 2022.

- ^ Franze, Kristian; Grosche, Jens; Skatchkov, Serguei N.; Schinkinger, Stefan; Foja, Christian; Schild, Detlev; Uckermann, Ortrud; Travis, Kort; Reichenbach, Andreas; Guck, Jochen (2007-05-15). "Muller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (20): 8287–8292. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611180104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1895942. PMID 17485670.

- ^ Sanders, Robert (2016-07-05). "Weird pupils let octopuses see their colorful gardens". Berkeley News. Archived from the original on 2016-07-06. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1892). The History of Creation. Appleton, New York: D. Appleton. p. 326.

- ^ Spreitzer RJ, Salvucci ME (2002). "Rubisco: structure, regulatory interactions, and possibilities for a better enzyme". Annu Rev Plant Biol. 53: 449–75. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135233. PMID 12221984. S2CID 9387705.

- ^ Ellis RJ (January 2010). "Biochemistry: Tackling unintelligent design". Nature. 463 (7278): 164–5. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..164E. doi:10.1038/463164a. PMID 20075906. S2CID 205052478.

- ^ Dembski, William (1999). Intelligent design: the bridge between science & theology. InterVarsity Press. p. 261. ISBN 0-8308-2314-X.

- ^ Martin, Loren G. (October 21, 1999). "What is the function of the human appendix?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012.

- ^ Isaak, Mark (2004). "Claim CB130". Talk.Origins. Archived from the original on 2006-09-11.

- ^ Hirotsune, S; Yoshida, N; Chen, A; Garrett, L; Sugiyama, F; Takahashi, S; Yagami, K; Wynshaw-Boris, A; Yoshiki, A.; et al. (2003). "An expressed pseudogene regulates the messenger-RNA stability of its homologous coding gene". Nature. 423 (6935): 91–6. Bibcode:2003Natur.423...91H. doi:10.1038/nature01535. PMID 12721631. S2CID 4360619.

- ^ Gray, TA; Wilson, A; Fortin, PJ; Nicholls, RD (2006). "The putatively functional Mkrn1-p1 pseudogene is neither expressed nor imprinted, nor does it regulate its source gene in trans". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103 (32): 12039–12044. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312039G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602216103. PMC 1567693. PMID 16882727.

- ^ "Google Scholar". scholar.google.com.

- ^ "The Panda's Peculiar Thumb". NATURAL HISTORY. November 1978. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28.

- ^ Collins, Francis S. The Language of God (New York: Simon & Schuster), 2006. p 191. ISBN 978-1-4165-4274-2

- ^ Mitchell, Dr. Elizabeth (15 November 2006). "The Evolution of Childbirth?". Answers in Genesis. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Avise, John C. (2010), Inside the Human Genome: A Case for Non-Intelligent Design, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-539343-0.

- Dawkins, Richard (1986). The Blind Watchmaker. ISBN 0-393-30448-5

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History. ISBN 0-393-30023-4

- Gurney, Peter W.G. (1999). "Is our 'inverted' retina really 'bad design'?". Creation Ex Nihilo Technical Journal/TJ. 13 (1): 37–44.

- Leonard, P. (1993). "Too much light," New Scientist, 139.

- Martin, B.; Martin, F. (2003). "Neither intelligent nor designed". Skeptical Inquirer. 27: 6.

- Perakh, Mark Unintelligent Design (ISBN 1-59102-084-0 – December 2003)

- Williams, Robyn (1 February 2007). Unintelligent Design: Why God Isn't as Smart as She Thinks She Is. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-923-4.

- Witt, Jonathan. "The Gods Must Be Tidy!", Touchstone, July/August 2004.

- Woodmorappe, J. (1999). "Why Weren't Plants Created 100% Efficient at Photosynthesis? (OR: Why Aren't Plants Black?)"

- Woodmorappe, J. (2003). "Pseudogene function: more evidence" Creation Ex Nihilo Technical Journal/TJ 17(2):15?18.