Royce Gracie

| Royce Gracie | |

|---|---|

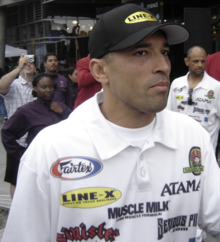

Gracie in 2018 | |

| Born | 12 December 1966 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Height | 6 ft 0 in (183 cm) |

| Weight | 176 lb (80 kg; 12 st 8 lb) |

| Division | Middleweight Light heavyweight Openweight |

| Reach | 194 cm (76 in) |

| Style | Gracie jiu-jitsu |

| Stance | Southpaw |

| Fighting out of | Torrance, California, United States |

| Team | Gracie Humaitá[1]

Team Royce Gracie |

| Teacher(s) | Hélio Gracie |

| Rank | 7th deg. BJJ coral belt (under Rickson Gracie[2]) |

| Years active | 1993–1995, 2000–2007, 2016 (MMA) 1998 (Submission grappling) |

| Mixed martial arts record | |

| Total | 20 |

| Wins | 15 |

| By knockout | 2 |

| By submission | 11 |

| By decision | 2 |

| Losses | 2 |

| By knockout | 2 |

| Draws | 3 |

| Other information | |

| Notable relatives | Gracie family |

| Website | roycegracie |

| Mixed martial arts record from Sherdog | |

Royce Gracie (Portuguese: [ˈʁɔjsi ˈɡɾejsi]; born 12 December 1966)[3] is a Brazilian retired professional mixed martial artist.[4] Gracie gained fame for his success in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). He is a member of the Gracie jiu-jitsu family, a UFC Hall of Famer, and is considered to be one of the most influential figures in the history of mixed martial arts (MMA).[5][6] He also competed in PRIDE Fighting Championships, K-1's MMA events, and Bellator.

In 1993 and 1994, Gracie was the tournament winner of UFC 1, UFC 2 and UFC 4, which were openweight single-elimination tournaments with minimal rules. He used his skills in submission grappling to defeat larger and heavier opponents.[7] He was also known for his rivalry with Ken Shamrock, whom he beat in UFC 1 and then fought to a draw in the rematch for the Superfight Championship at UFC 5.[8] Royce later competed in PRIDE Fighting Championships, where he is most remembered for his 90-minute bout against catch wrestler Kazushi Sakuraba in 2000,[9] and a controversial "judo vs jiu-jitsu" mixed rules match against Hidehiko Yoshida, an Olympic gold medalist in judo, at PRIDE Shockwave in 2002.[10]

Royce Gracie's success in the UFC popularized Gracie jiu-jitsu (commonly referred to as "Brazilian" jiu-jitsu) and revolutionized mixed martial arts, contributing to the movement towards grappling and ground fighting.[7] For his pioneering in mixed martial arts, Gracie was the first inductee to the UFC Hall of Fame in 2003 alongside his once-rival Ken Shamrock.[11] In 2016, he was inducted into the International Sports Hall of Fame.[12]

Early life

[edit]Royce Gracie was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on 12 December 1966. One of the nine sons of jiu-jitsu grandmaster Hélio Gracie, he learned the martial art from his father in his childhood.[13] He had his first competition at age 8 and started teaching classes when he was 14 years old. When he was 17, Royce was awarded a black belt by his father, Hélio.[14] A few months later, he and his brothers Royler and Rickson Gracie moved to Torrance, California, to live with their older brother Rorion Gracie, who had moved there in 1978 and had established Gracie Academy.[15]

The Gracie brothers in the United States continued the family's tradition of the "Gracie Challenge", in which they challenged other martial artists to no-rules full-contact matches in their gym to prove the superiority of Gracie jiu-jitsu.[16] Rorion would later edit footage from the Gracie Challenge fights into a single documentary series known as Gracie in Action, with some footage featuring Royce's fights.[17] The Gracie in Action tapes inspired Art Davie to create the UFC.[18]

Mixed martial arts career

[edit]Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC)

[edit]UFC 1

[edit]The Ultimate Fighting Championship was founded in 1993 by Rorion Gracie, business executive Art Davie, and the Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG). The premise of the event was doing an eight-man openweight single-elimination tournament, with minimal rules, from fighters representing different martial arts, to find the most effective and strongest fighting style. While Davie and the SEG were interested in doing an event with violent and exciting vale tudo fights similar to what they had seen on the Gracie in Action tapes, Rorion was interested in promoting his family's own jiu-jitsu style by defeating larger and stronger opponents from more well-known martial arts. Rorion said he picked Royce to represent the family's art because of his skinnier and smaller frame, to show how a small person can defeat a bigger opponent using jiu-jitsu.[19]

Gracie entered the tournament wearing his now iconic Brazilian jiu-jitsu gi.[7] In his first match, Gracie defeated journeyman boxer Art Jimmerson. He tackled him to the ground using a baiana (morote-gari or double-leg) and obtained the dominant "mounted" position. Mounted and with only one free arm, Jimmerson conceded defeat.

In the semi-finals, Gracie fought against shootfighter and King of Pancrase fighter Ken Shamrock. This was Royce's most difficult match, as Shamrock had grappling experience (having caught Patrick Smith in a Heel Hook in a previous match). Gracie started the round by attempting a double-leg, which was defended by Shamrock with a sprawl, and Shamrock attempted to stand up back to his feet. Gracie then responded by pulling Shamrock to his guard and started to do small kicks into Shamrock's kidneys, but he got out from his guard and attempted to pull Gracie into a heel hook, as he had done with Patrick Smith similarly before. The Brazilian defended by wrapping his gi around Shamrock's arm, and when the latter sat back, it pulled Gracie on top of him. He then proceeded to take Shamrock's back and used his own gi to secure a rear naked choke.[20] Shamrock later stated it was a gi choke, using the cloth around his neck.[21] Shamrock tapped out to Gracie's choke, but the referee did not see the tap and ordered both fighters to continue the match. Shamrock then admitted defeat to the referee, saying it would not be fair, and Royce was declared the bout's victor, with both fighters exchanging a handshake after some taunting.[22]

Gracie fought in the finals against karate Kyokushin practitioner and savate world champion Gerard Gordeau. Gracie managed to take his opponent to the ground and secure a rear choke, winning the bout.[23] During the fight, Gordeau bit Gracie's ear, breaking one of the few rules of the event.[24] Gracie retaliated by holding the choke after Gordeau had tapped out, with the Dutchman tapping in panic before they were separated by the referee.[25] Royce was then declared the "Ultimate Fighting Champion" and was awarded $50,000 in prize money.[23]

Rivalry with Ken Shamrock

[edit]After Gracie defeated Ken Shamrock in the first UFC event, a rivalry developed between the fighters. Shamrock especially wanted a rematch as,[8] according to him, Gracie had used the gi to favor his grappling while he had not been allowed to use wrestling shoes by the promoters, which he considered an unfair advantage to Gracie.[26] Shamrock nonetheless conceded that he had underestimated his opponent.[27]

A rematch between Royce Gracie and Ken Shamrock failed to materialize at the UFC 2, as Shamrock had broken his hand in training[28] and at UFC 3 Gracie withdrew from the competition due to exhaustion (resulting in Shamrock withdrawing from the event too). To solve the problem of the tournament format's unpredictability, a "superfight" in which Gracie and Ken Shamrock would fight in a bout outside the main tournament was scheduled for the UFC 5.[8]

UFC 2

[edit]Gracie returned to defend his title four months later at UFC 2, this tournament would have sixteen fighters and he would have to defeat four opponents to become the champion.[5] Gracie began his defense of the title by submitting Japanese Karatedo Daido Juku and Kyokushin karateka Minoki Ichihara after a five-minute bout, his longest yet,[29] with a lapel choke (which was possible as Ichihara was wearing a Karategi).[30] Advancing into the quarterfinals, Royce Gracie fought Five Animals Kung Fu practitioner and future Pancrase veteran Jason DeLucia, whom he had already fought and defeated before in one of the "Gracie Challenges" in 1991. Gracie submitted DeLucia via armbar just over a minute into the bout.[31] Gracie then submitted 250-lb Judo and Taekwondo black belt Remco Pardoel with a lapel choke (as Pardoel was wearing a Judogi),[32][33] and arrived at the finals against kickboxer Patrick Smith, who had previously participated at UFC 1. Showing his superior grappling skills, Gracie easily took Smith to the ground and won the fight via submission to punches.[34]

UFC 3

[edit]Royce Gracie entered UFC 3 now as twice-champion and as the favorite to win. The number of fighters was scaled down back to eight like the first edition.[35] Royce was matched up in the first round against Kimo Leopoldo, a representative of Taekwondo and former high school wrestler. Leopoldo used his wrestling background to dominate the grappling exchanges, denying several of Gracie's takedowns and even took his back. As both men began to tire, Gracie held down Leopoldo by grabbing onto his pony tail, eventually submitting him with an armbar at 4:40 of round one.[36] However, he withdrew from his next fight with Harold Howard before it began due to exhaustion and dehydration.[35] Royce entered the ring and threw in the towel.[37] This was the first event which Gracie did not win.

UFC 4

[edit]Gracie began UFC 4 by submitting 51-year-old Karateka and Kung Fu film actor Ron van Clief in the opening round with a rear-naked choke near the four-minute mark. In the semi-finals, he fought American Kenpo Karate specialist Keith Hackney, who was able to defend Gracie's takedowns for four minutes until he was submitted by an armbar.[38]

Gracie's final tournament bout was against Dan Severn, a former Pan American freestyle wrestling gold medalist. Severn dominated the fight, securing takedowns and maintaining top control throwing ground and pound for nearly fifteen minutes. However Gracie eventually managed to secure a triangle choke for the submission victory at 15:49 of round one.[38] The match extended beyond the pay-per-view time slot and viewers, who missed the end of the fight, demanded their money back.

UFC 5

[edit]Gracie and Shamrock returned for UFC 5, they were both set to headline the UFC's first "superfight", a special outside the main tournament to rematch Gracie and Shamrock, as they would have no prior damage from a previous fight. The winner would win a special belt and become the inaugural UFC Superfight Champion.[8] Time limits were re-introduced into the sport in 1995 due pay-per-view limits after the UFC 4 debacle and the fighters were only told a few hours before the event, upsetting both competitors.

At the start of round one, Shamrock immediately scored a takedown with Gracie pulling guard. The majority of the contest consisted of Shamrock in top position defending Gracie's submission game, occasionally landing ground and pound. After nearly thirty minutes of control time for Shamrock, the contest was given overtime and restarted on the feet. At the beginning of the overtime, Shamrock connected with a punch that led to swelling on Gracie's eye, with Gracie immediately pulling guard. After another uneventful few minutes, the contest was declared a draw.[8][39]

The draw sparked much debate and controversy as to who would have won the fight had judges determined the outcome, or had there been no time limits, as by the end of the fight Gracie's right eye was swollen shut.[40] Had there been ringside judges, UFC matchmaker Art Davie believes that Shamrock would have been declared the winner.[39] The fight was poorly received by critics and the live audience, due to the lack of action from both competitors.[8]

After the fight, Gracie left the UFC along with his brother Rorion, who sold his shares of the event. According to Rorion, they left the organization due a conflict of interest because of the time limits introduced after UFC 4 and future plans to introduce judges, and weight classes.[41]

Royce's challenge letters

[edit]Throughout his UFC days, Royce frequently challenged well-known fighters—though usually to no avail—to "fight to the finish, any place and any time." Many big-name sportspeople, including Mike Tyson (who was serving a prison term at the time) received a note several times in an open letter fashion, usually published by Black Belt Magazine in The Ultimate Fighter column.[42][43]

UFC Hall of Fame

[edit]At UFC 45 in November 2003, at the ten-year anniversary of the UFC, Shamrock and Gracie became the first inductees into the UFC Hall of Fame. UFC President Dana White said;[11]

We feel that no two individuals are more deserving than Royce and Ken to be the charter members. Their contributions to our sport, both inside and outside the Octagon, may never be equaled.

PRIDE Fighting Championships

[edit]Attempts to sign Royce

[edit]Gracie was originally going to debut in PRIDE Fighting Championships in their 1998 PRIDE 2 event, where he would be pitted against fellow UFC champion Mark Kerr. The Gracie side demanded special rules without time limit or referee stoppage, which were accepted.[44] However, Royce pulled out due to a back injury after the fight had been advertised.[45]

The situation changed after PRIDE 8, when Royce's older brother Royler Gracie was defeated by Kazushi Sakuraba. Sakuraba dominated the match and won by technical submission, as Royler was caught in a Kimura lock and refused to tap out, the referee stopped the match before his arm could be broken.[46] This was the first time in 50 years a Gracie had been defeated in a mixed martial arts fight and Sakuraba followed by a challenge to Rickson Gracie.[46] In response, the Gracies argued that Royler's loss did not count as he had not conceded or tapped out, and the referee's stopping of the bout went against the special ruleset they had requested for the fight. Many pundits were also affirming that the Gracie pure-BJJ approach was not able to match a well-rounded cross-trained fighter anymore.[46] In response to that assertion, and to defeat Sakuraba in a rematch, the Gracies signed Royce up to PRIDE.[47]

PRIDE Grand Prix and bout against Nobuhiko Takada

[edit]Royce Gracie's first event in PRIDE was in the "PRIDE Grand Prix 2000", an openweight tournament that would be divided into two events: the Opening Round, which consisted of the Round of 16 and the Finals which would happen three months later and consisted of the quarter-finals, Semi-finals and Finals. The bouts in the Opening Round had their rules modified to have only one round of fifteen minutes.[48] In the first round, he fought Japanese professional wrestler Nobuhiko Takada. Takada was a very popular wrestler who had headlined PRIDE 1 and PRIDE 4 against Royce's brother Rickson.[49] Takada was also the former mentor of Sakuraba, the family's rival.[46]

In the first minute of the bout Gracie pulled Takada into his guard, and he spent the rest of the match unsuccessfully trying to submit or sweep Takada.[49] After a largely uneventful fight, Royce Gracie was declared the winner by unanimous decision and advanced to the Grand Prix Quarter-Finals.[49][50]

Bout with Sakuraba

[edit]Royce was then set to fight Kazushi Sakuraba in the quarter-finals at the PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 Finals. Sakuraba was a professional wrestler who derived his foundation in submissions from catch wrestling and shoot wrestling. He had defeated several opponents and become one of the first Japanese stars of PRIDE. As Royce entered the Grand Prix specially to fight Sakuraba, the Gracies demanded special rules for the fight: an unlimited number of 15-minute rounds, no judges, no referee stoppages, and wins could only come by knockout, submission or throwing in the towel.[46][51] Sakuraba criticized the different ruleset, the Gracie's demands to fight under it and their demands for special treatment, but ended up agreeing to the challenge nonetheless.[51]

The two battled for an hour and a half, after which Gracie began to fatigue, and could no longer stand due to a broken femur as a result of numerous leg kicks. The towel was thrown in and Sakuraba was declared the winner. Sakuraba went on to defeat other members of the Gracie family, including Renzo Gracie and Ryan Gracie, earning him the nickname "Gracie Hunter."[52]

Bouts with Yoshida

[edit]Gracie returned to PRIDE in 2002 to fight Japanese gold-medalist judoka Hidehiko Yoshida in a special "judo vs. Brazilian jiu-jitsu" special rules match, billed as a "rematch" of Masahiko Kimura vs. Hélio Gracie, which had happened 50 years earlier. The rules were that the fight would be contested in two 10-minute rounds and would be declared a draw if no result was achieved. Strikes to the head were disallowed, as it was any kind of strike if both opponents were on the ground. Lying on the mat or dropping down without touching the opponent would be banned as well. Both fighters would wear a keikogi as per their respective disciplines's preference.[53] It happened at PRIDE Shockwave a co-production between PRIDE and K-1 kickboxing, intended to be a mega-event celebrating martial arts, with the event still having the largest live attendance in MMA history, drawing almost 91,000 fans[54] (with some sources suggesting instead 71,000).[55] Royce's father Hélio Gracie lit a ceremonial olympic torch along with MMA pioneer Antonio Inoki in the opening ceremony.[54]

Royce started the fight pulling guard and attempting a heel hook and an armbar, with Hidehiko blocking them and coming back with a gi choke and an ankle lock attempt. Gracie pulled guard again, but Yoshida turned it into a daki age and sought the Kimura lock; then, when the Brazilian blocked the technique, Yoshida passed his guard and performed a mounted sode guruma jime. After a moment of inactivity, the referee Daisuke Noguchi stopped the match in the belief Royce was unconscious and gave victory to Yoshida.[54]

Gracie immediately protested and footage of the fight was reviewed, which showed that Gracie's visible arm during the execution of the choke was limp and motionless.[54] Gracie began to argue with Noguchi, the squabble soon resulted in him attacking the referee and it escalated into a full a brawl between the corners of the two fighters.[56][10] Later backstage, the Gracies demanded it be turned into a no contest, and an immediate rematch be booked with different rules. If not, the Gracie family would never fight for PRIDE FC again.[57] PRIDE, wanting to keep the Gracie family with them, accepted their demands.

Afterward, Gracie started fighting without a gi so that his opponents could not stall by holding onto it. The grudge match between Yoshida and Gracie took place at PRIDE's Shockwave 2003 event on December 31, 2003. Gracie dominated Yoshida but, as the match had no judge per Gracie's request, the bout was declared a draw after two 10-minute rounds.[58]

Fighting and Entertainment Group

[edit]In September 2004 PRIDE had a disagreement with Gracie about his participation in the 2005 PRIDE Middleweight Grand Prix. Gracie had issues with the proposed opponents and rules (Grand Prix fights must have a winner and cannot end in a draw). He jumped to Fighting and Entertainment Group's K-1 organization. Pride sued Gracie for breaching his contract with them. The case was settled in December 2005, with Gracie issuing a public apology, blaming his actions on a misinterpretation of the contract by his manager.

In K-1, Royce Gracie competed on K-1's Dynamite!! series, which featured both kickboxing and MMA matches on their cards. On December 31, 2004, Gracie entered the K-1 scene at the K-1 PREMIUM 2004 Dynamite!! event inside the Osaka Dome, facing off against former sumo wrestler and MMA newcomer Akebono Tarō aka. Chad Rowan under special MMA rules (Two 10-minute rounds; the match would end as a draw if there was no winner after the two rounds). Gracie made quick work of his heavy opponent, forcing Akebono to submit to a shoulder lock at 2:13 of the first round.

Exactly one year later, on the K-1 PREMIUM 2005 Dynamite!! card of December 31, 2005, Gracie fought Japan's Hideo Tokoro, a 143-pound fighter, in a fight ending in a draw after 20 minutes. Gracie's original opponent was scheduled to be the tall Korean fighter Choi Hong-man, another MMA newcomer.

Return to UFC

[edit]On January 16, 2006, UFC President Dana White announced that Royce Gracie would return to the UFC to fight UFC welterweight champion Matt Hughes on May 27, 2006, at UFC 60. This was a non-title bout at a catchweight of 175 lb. under UFC/California State Athletic Commission rules. To prepare, Gracie trained in Muay Thai and was frequently shown in publicity materials from Fairtex.[59]

In round one, Hughes secured a straight armbar that hyper-extended Royce's arm, however Royce refused to tap. Hughes eventually won the fight by TKO at 4:39 of the first round.[60][61]

Royce said later after the fight with Hughes that he wanted a rematch and that he was not surprised by Hughes's performance: "No, we knew what he was planning to do. We worked out his gameplan before the fight, and he did exactly what we expected. I over-trained for the fight. That was all. I started training too much, too hard, for too long. He did exactly what we expected."[62]

Rematch with Sakuraba

[edit]On May 8, 2007, EliteXC announced that Gracie's opponent for the June 2 Dynamite!! USA event in Los Angeles would be Japanese fighter Kazushi Sakuraba.

Gracie defeated Sakuraba by a unanimous decision. However, a post-fight drug screen revealed that Royce had traces of Nandrolone in his system. "Use of steroids is simply cheating," said Armando Garcia, California State Athletic Commission executive director. "It won't be tolerated in this state."[63]

Steroids scandal

[edit]On June 14, 2007, the California State Athletic Commission declared that Gracie had tested positive for Nandrolone, an anabolic steroid, after his fight with Sakuraba.[63] According to the California State Athletic Commission, the average person could produce about 2 ng/ml of Nandrolone, while an athlete following "rigorous physical exercise" could have a level of around 6 ng/ml.[64] Both "A" and "B" test samples provided by Gracie "had a level of over 50 ng/ml and we were informed that the level itself was so elevated that it would not register on the laboratory's calibrator," said the CSAC.[65] Gracie was fined $2,500 (the maximum penalty the commission can impose) and suspended for the remainder of his license, which ended on May 30, 2008. Gracie paid the fine.[66]

Royce Gracie decided to dispute the allegations during an online video interview in May 2009, saying that his weight in the first UFC event was 178 lb and claiming his weight during his Sakuraba fight was 180 lb, thus only gaining 2 pounds.[67] This was widely disputed by experts. According to ESPN, "In the former contest, he weighed in at 175 pounds; for Sakuraba, he was 188. One may not need to be nutritionist to observe that a muscle gain of 13 pounds in one year at the age of 40 is a strikingly accomplished feat. Athletes nearing the half-century mark are often happy to maintain functional mass, let alone pack it on".[68]

Retirement

[edit]

On March 11, 2011, Royce Gracie's profile was added back to ufc.com active fighters list as a middleweight. His manager stated that they were actively negotiating with the UFC for a return to the Octagon and said it was just a matter of "getting it nailed down" and that there was plenty of time for it.[69] On November 15, 2013, at UFC 167 on the 20th Anniversary of the UFC, Royce Gracie confirmed to MMA journalist Ariel Helwani that he had retired from competing in mixed martial arts.[3]

Return with Bellator MMA

[edit]At Bellator 145, it was announced that Gracie would return from retirement to face rival Ken Shamrock in a trilogy fight, taking place on February 19, 2016, at Bellator 149.[70] Gracie won the fight via TKO in round one.[71] The win was not without controversy, however, as replays showed that Gracie landed a knee strike that grazed the groin of Shamrock prior to the finish. Shamrock protested the stoppage, however the bout was officially ruled a victory for Gracie.[72] It was later announced that Shamrock had failed his pre-fight drug test for banned substances.[73]

Submission grappling career

[edit]On December 17, 1998, at Oscar de Jiu Jitsu, Royce Gracie competed in a grudge-match superfight against Wallid Ismail in front of several thousand spectators. Carlson Gracie was Ismail's coach, though Ismail originally was Carlson's fourth choice to face Royce after Mario Sperry, Murilo Bustamante and Amaury Bitetti. The match was contested without points and with no time-limit in place, with Ismail choking Gracie unconscious via clock choke in four minutes and fifty-three seconds.[74][75][76][77]

Post-fight career

[edit]

Gracie has been since retired from MMA competition and has been focusing in teaching jiu-jitsu. He mostly travels around the world going to schools, teaching in seminars and doing interviews in magazines, websites and talk shows.[78] He has opened his own association of gyms known as "Royce Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Network", with affiliate schools in 34 locations in the United States, and many throughout the world in Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, Guatemala, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.[79]

Royce Gracie's branch of jiu-jitsu focuses mainly on the self-defense parts of the martial art. Gracie has accused modern "sporting" jiu-jitsu of teaching techniques that are unpractical and unrealistic to use in a self-defense situation, and claims to be rescuing the true intent of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu as devised by his father Hélio Gracie.[80]

Personal life

[edit]Gracie filed for divorce in 2016. He and his former wife Marianne have three sons and a daughter.[81] His son Kheydon Gracie enlisted in the US Army.[82]

Despite being a 7th degree coral belt, Gracie wears a dark blue belt when training in Brazilian jiu-jitsu paying homage to his father, Hélio Gracie, who primarily wore a dark blue belt despite having the highest possible rank, red belt. Hélio Gracie died in 2009, and Royce said he does not want to be promoted by anybody else.[83]

He has formerly identified as a Zionist and a supporter of Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro.[84][85]

Gracie is an avid firearms shooter. In 2022, Gracie competed in and was on the winning team of the Sig Hunter Games as a member of team Warrior.[86]

On July 6, 2023, it was announced that ESPN Films is producing a documentary series on the Gracie family directed by Chris Fuller and produced by Greg O'Connor and Guy Ritchie.[87]

Controversies and legal troubles

[edit]Gracie has engaged in multiple disputes with other martial artists including his nephews Rener Gracie, Ryron Gracie,[88] and Eddie Bravo.[89]

On April 1, 2015, the IRS sent Royce Gracie and his wife a Notice of Deficiency claiming they owe $657,114 in back taxes and $492,835.25 in penalties for Civil Fraud, based on IRC 6663(a).[90] The case was settled on March 31, 2023, and Royce Gracie agreed to pay $461,611.80 to the US government.[91]

Instructor lineage

[edit]Brazilian jiu-jitsu

[edit]Kano Jigoro → Tomita Tsunejiro → Mitsuyo Maeda → Carlos Gracie → Hélio Gracie → Royce Gracie[92]

Career accomplishments

[edit]Mixed martial arts

[edit]- Ultimate Fighting Championship

- UFC Hall of Fame (Inaugural inductee, Pioneer Wing, class of 2003)

- UFC 1 Tournament Championship

- UFC 2 Tournament Championship

- UFC 4 Tournament Championship

- UFC 3 Tournament semi-finalist[a]

- UFC Encyclopedia Awards

- Fight of the Night (Four times) vs. Ken Shamrock 1, Minoki Ichihara, Kimo Leopoldo and Dan Severn[93][94][95][96]

- Submission of the Night (Four times) vs. Gerard Gordeau, Remco Pardoel, Kimo Leopoldo and Dan Severn[93][94][95][96]

- UFC Viewer's Choice Award[97]

- First tournament champion in UFC history

- Longest finish streak in UFC history (11)[98]

- Most bouts won in tournaments in UFC history (11)

- Most tournaments won in UFC history (3)

- Most fights in a single night in UFC history (4) (tied with Patrick Smith)

- Longest fight in UFC history (36 minutes) - vs. Ken Shamrock 2 at UFC 5

- Longest submission streak in UFC history (6)[99]

- Tied (Gilbert Burns) for most armbar submission wins in UFC history (4)[100]

- Third highest submission finish rate in UFC history (10 submissions / 11 wins - 90.91%)

- Greatest Submission in UFC's first 25 Years[101] - vs. Ken Shamrock 1

- PRIDE Fighting Championships

- Longest fight in PRIDE history (90 minutes) - vs. Kazushi Sakuraba at PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 Finals

- Fight Matrix

- Fighter of the Year (1993)[102]

- Black Belt Magazine

- Competitor of the Year (1994)[103]

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Fight of the Year (2000) - vs. Kazushi Sakuraba on May 1

- World MMA Awards

- 2013 Lifetime Achievement[104]

- International Sports Hall of Fame

- Class of 2016

Mixed martial arts record

[edit]| 20 matches | 15 wins | 2 losses |

| By knockout | 2 | 2 |

| By submission | 11 | 0 |

| By decision | 2 | 0 |

| Draws | 3 | |

| Res. | Record | Opponent | Method | Event | Date | Round | Time | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 15–2–3 | Ken Shamrock | TKO (knee and punches) | Bellator 149 | February 19, 2016 | 1 | 2:22 | Houston, Texas, United States | Light heavyweight bout. |

| Win | 14–2–3 | Kazushi Sakuraba | Decision (unanimous) | Dynamite!! USA | June 2, 2007 | 3 | 5:00 | Los Angeles, California, United States | Catchweight (188 lb) bout. Gracie tested positive for anabolic steroids after match. The judges' decision was not overturned.[105] |

| Loss | 13–2–3 | Matt Hughes | TKO (punches) | UFC 60 | May 27, 2006 | 1 | 4:39 | Los Angeles, California, United States | Catchweight (175 lb) bout. |

| Draw | 13–1–3 | Hideo Tokoro | Draw | K-1 PREMIUM 2005 Dynamite!! | December 31, 2005 | 2 | 10:00 | Osaka, Japan | Rules modified for no judges' decision. |

| Win | 13–1–2 | Akebono Taro | Submission (omoplata) | K-1 PREMIUM 2004 Dynamite!! | December 31, 2004 | 1 | 2:13 | Osaka, Japan | |

| Draw | 12–1–2 | Hidehiko Yoshida | Draw (time limit) | PRIDE Shockwave 2003 | December 31, 2003 | 2 | 10:00 | Saitama, Japan | Rules modified for no referee stoppages and no judges' decision. |

| Loss | 12–1–1 | Kazushi Sakuraba | TKO (corner stoppage) | PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 Finals | May 1, 2000 | 6 | 15:00 | Tokyo, Japan | 2000 PRIDE Openweight Grand Prix Quarterfinal; Rules modified for unlimited rounds and no referee stoppages. |

| Win | 12–0–1 | Nobuhiko Takada | Decision (unanimous) | PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 Opening Round | January 30, 2000 | 1 | 15:00 | Tokyo, Japan | |

| Draw | 11–0–1 | Ken Shamrock | Draw (time limit) | UFC 5 | April 7, 1995 | 1 | 36:00 | Charlotte, North Carolina, United States | For the inaugural UFC Superfight Championship. Match was declared a draw due to lack of judges. Longest fight in UFC history. |

| Win | 11–0 | Dan Severn | Submission (triangle choke) | UFC 4 | December 16, 1994 | 1 | 15:49 | Tulsa, Oklahoma, United States | Won the UFC 4 Tournament. Became the first and only three time UFC Tournament Winner. |

| Win | 10–0 | Keith Hackney | Submission (armbar) | 1 | 5:32 | UFC 4 Tournament Semifinal. | |||

| Win | 9–0 | Ron van Clief | Submission (rear-naked choke) | 1 | 3:59 | UFC 4 Tournament Quarterfinal. | |||

| Win | 8–0 | Kimo Leopoldo | Submission (armbar) | UFC 3 | September 9, 1994 | 1 | 4:40 | Charlotte, North Carolina, United States | UFC 3 Tournament Quarterfinal. Gracie withdrew from tournament afterwards. |

| Win | 7–0 | Patrick Smith | TKO (submission to punches) | UFC 2 | March 11, 1994 | 1 | 1:17 | Denver, Colorado, United States | Won the UFC 2 Tournament. |

| Win | 6–0 | Remco Pardoel | Submission (lapel choke) | 1 | 1:31 | UFC 2 Tournament Semifinal. | |||

| Win | 5–0 | Jason DeLucia | Submission (armbar) | 1 | 1:07 | UFC 2 Tournament Quarterfinal. | |||

| Win | 4–0 | Minoki Ichihara | Submission (lapel choke) | 1 | 5:08 | UFC 2 Tournament Opening Round. | |||

| Win | 3–0 | Gerard Gordeau | Submission (rear-naked choke) | UFC 1 | November 12, 1993 | 1 | 1:44 | Denver, Colorado, United States | Won the UFC 1 Tournament. |

| Win | 2–0 | Ken Shamrock | Submission (rear-naked choke) | 1 | 0:57 | UFC 1 Tournament Semifinal. | |||

| Win | 1–0 | Art Jimmerson | Submission (smother choke) | 1 | 2:18 | UFC 1 Tournament Quarterfinal. |

Submission grappling record

[edit]See also

[edit]- Gracie family

- Rodrigo Gracie

- List of doping cases in sport

- List of Brazilian jiu-jitsu practitioners

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gracie withdrew from the tournament due to injury.

References

[edit]- ^ "Royce Gracie MMA Stats, Pictures, News, Videos, Biography". Sherdog.com. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Explains Why He Wears a Blue Belt instead of a Coral Belt". BJJEE.com. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b "UFC 167: Royce Gracie on UFC 1, Renzo Gracie's Criticism, More". YouTube. 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2014-04-04.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ "Nineteen years later, Royce Gracie reflects on UFC 1". MMA Fighting. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ a b Fusco, Anthony (September 24, 2012). "Why Royce Gracie Is the Most Influential MMA Fighter of All Time". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ "Full list: Royce Gracie among 50 greatest athletes of all time". MMA Junkie. 2014-01-14. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ a b c Rondina, Steven. "Royce Gracie's Legacy, BJJ's Relevance on the Decline in Modern MMA". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Meltzer, Dave (2016-02-19). "Gracie-Shamrock 2 held UFC PPV record for decade". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Mixed Martial Arts at the Turn of the Century". Fightland. 2015-01-08. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ a b Snowden, Jonathan; Shields, Kendall; Lockley, Peter (November 1, 2010). The MMA Encyclopedia. ECW Press. ISBN 978-15-502292-3-3.

- ^ a b "Zuffa Creates "Hall of Fame" with Shamrock, Gracie Charters". Sherdog.com. 2003-11-05. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ Dr. Robert Goldman (March 15, 2016). "2016 International Sports Hall of Fame Inductees". www.sportshof.org. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Explains Why He Won't Wear a Coral Belt But instead Wears a Blue Belt". Bjj Eastern Europe. 2021-09-08. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Royce Gracie". BJJ Heroes. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Grant, T. P. "History of Jiu-Jitsu: Coming to America and the Birth of the UFC". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Black Belt. Active Interest Media, Inc. April 1992.

- ^ "The Old School Gracie Challenge Videos Are Still a Must See! - Gracie Castle Hill". 8 December 2016. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Gentry III, Clyde, No Holds Barred: Ultimate Fighting and the Martial Arts Revolution, Milo Books, 2003, paperback edition, ISBN 1-903854-30-X, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Cruz, Guilherme (2013-11-12). "Rorion Gracie and the day he created the UFC". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Krauss, Erich (November 10, 2010). Brawl: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Mixed Martial Arts Competition. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1554902385.

- ^ "Japan's Rich MMA History: The Ken Shamrock Interview, Part 5 of 7". Mixedmartialarts.com. September 20, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Ken Shamrock and Royce Gracie". MMAMemories.com. December 14, 2007. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Don Beu, The Ultimate Fighting Championship: Jujutsu and Royce Gracie Reign Supreme at No-Holds-Barred Tournament, Black Belt magazine, March 1994

- ^ Rogers, Kian (26 April 2023). "Throwback: Watch Royce Gracie On His Legendary UFC 1 Run". JitsMagazine. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Jokes About Getting Bit And Holding Choke At UFC 1". 2020-08-17. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Japan's Rich MMA History: The Ken Shamrock Interview, Part 5 of 7". Mixedmartialarts.com. September 23, 2015. Retrieved Oct 24, 2021.

- ^ "Japan's Rich MMA History: The Ken Shamrock Interview, Part 5 of 7 » MixedMartialArts.com". www.mixedmartialarts.com. 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ^ "About Ken Shamrock". Lionsdenreno.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ Saccaro, Matt. "The 11 Most Important Figures in MMA That You've Probably Never Heard of". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ Gorman, Jeff D. "UFC 2: Solving the Royce Gracie Riddle". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

His wish is granted as Gracie smothers him and starts nailing him with punches to the ribs and palm strikes to the face. The announcers talk about how Gracie wants to win via choke, but it's not happening. Realizing that he has to fight three more times, Gracie switches to a lapel choke and gets the tap out.

- ^ Wynne, Lucy (2021-09-12). "WATCH: Royce Gracie Try to Break Arm After Tap on UFC 2". Grappling Insider. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Bjj Eastern Europe – UFC 2 Vet Remco Pardoel On Pioneering BJJ In Europe, Fighting In The First Mundials In The Black Belt Division & His Flourishing DJ Career". Bjjee.com. 2013-03-20. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Gorman, Jeff D. "UFC 2: Solving the Royce Gracie Riddle". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

Gracie is giving up 84 pounds, so it takes a long time to bring Pardoel down, but he finally does. Pardoel tries for a kimura, but Gracie uses the gi to choke the big man out.

- ^ "Royce Gracie vs Patrick Smith Fight Result Videos UFC 2".

- ^ a b "Today in MMA History: When Royce Gracie couldn't continue and all hell broke loose". mmajunkie.com. 9 September 2018.

- ^ Newman, Scott (2005-06-11). "MMA Review: #52: UFC 3: The American Dream". The Oratory. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- ^ Snowden, Jonathan; Shields, Kendall (November 2010). The MMA Encyclopedia. ECW Press. ISBN 9781554908448.

- ^ a b Abraham, Joel. "UFC 4 Review: Royce Gracie's Revenge and Dan Severn's Debut". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ a b "'Legend fights' scoring big for Bellator MMA". ESPN.com. February 15, 2016.

- ^ Blackbelt Magazine May 1995

- ^ Cruz, Guilherme (2016-07-12). "UFC founder Rorion Gracie reacts to UFC sale". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "How's Mike Tyson for a Big Name? (An Open-letter by Royce Gracie)". Black Belt. 32 (12): 15. December 1994.

- ^ "What's the Matter, Tyson... Are You Chicken? (An Open-letter by Royce Gracie)". Black Belt. 34 (6): 16. June 1996.

- ^ Pride: The Secret Files (in Japanese). Kamipro. 2008.

- ^ Snowden, Jonathan (2012). Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. ISBN 978-17-709022-1-3.

- ^ a b c d e Snowden, Jonathan (December 1, 2008). Total MMA: Inside Ultimate Fighting. ECW Press. ISBN 978-15-549033-7-5.

- ^ "Mixed Martial Arts at the Turn of the Century". Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Pride FC - Pride Grand Prix 2000: Opening Round". Sherdog. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ a b c Slack, Jack (2017-07-03). "Nobuhiko Takada: MMA's Most Important Bad Fighter". Vice. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "Royce Gracie vs. Nobuhiko Takada, Pride Grand Prix 2000 Opening Round | MMA Bout".

- ^ a b Rosen, Jake (June 23, 2010). "Pride and Glory - Intermission". Sherdog. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Snowden, J.; Shields, K. (2010). The MMA Encyclopedia. ECW Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-1-55490-844-8.

- ^ Ihara, Yoshinori (June 16, 2002). "[Dynamite!] 8.28 国立 (会見):吉田秀彦×ホイス・グレイシー決定。50年前のルールを再現". Bout Review (in Japanese). Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Keith Vargo, Courage and Controversy reign at Shockwave event, Black Belt Magazine, January 2003

- ^ "Total Attendance". Tapology.

- ^ Black Belt. Active Interest Media. January 2003.

- ^ "Helio Gracie, Royce Gracie, Pedro Valente Interview 2002 GTR". www.global-training-report.com.

- ^ "Pride Shockwave 2003 | MMA Event".

- ^ "Muay Thai Training & Equipment - Fairtex Official". www.fairtex.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2006.

- ^ "Fairtex.com". Sherdog.com. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ Matt Hughes vs Royce Gracie – How the Battle of Champions Went Down – by Cliff Montgomery, ExtremeProSports.com

- ^ "Royce Gracie Wants a Rematch with Matt Hughes". MMAWeekly.com. August 10, 2006. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ^ a b "Royce Gracie Suspended, Fined For Steroids". Thesweetscience.com. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ "Gracie suspended after positive Nandrolone test". ESPN.com. 2007-06-15.

- ^ Gracie Opts Against Appealing – by Josh Gross. July 16, 2007

- ^ "Sporting News – Your expert source for MLB Baseball, NFL Football, NBA Basketball, NHL Hockey, NCAA Football, NCAA Basketball and Fantasy Sports scores, blogs, and articles". Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Video". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Gracie tests positive for off-the-chart measurements of steroids - MMA - ESPN". ESPN. 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ "Manager optimistic on Royce Gracie's UFC return, negotiations ongoing | MMAjunkie.com". mmajunkie.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Bellator books Royce Gracie vs. Ken Shamrock 3, 'Kimbo' vs. 'Dada 5000' for Houston - MMAjunkie". MMAjunkie. 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Bellator 149 results: Royce Gracie stops Ken Shamrock, but not without controversy". MMA Junkie. 2016-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ "Bellator 149 Results: Royce Gracie Defeats Ken Shamrock Amidst Controversy | MMAWeekly.com". 2016-02-20. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Raimondi, Marc (2016-03-11). "Slice, Shamrock fail drug tests at Bellator 149". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ "Oscar de Jiu Jitsu II". On The Mat | Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, MMA, News, Gear and Kimonos. September 6, 2004. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ Coffeen, Fraser (2011-08-26). "Royce Gracie vs. Wallid Ismael in a Jiu Jitsu Classic". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ de Souza, Diogo (22 May 2023). "Throwback: Watch Wallid Ismail Defeat Royce Gracie". Jitsmagazine. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Alonso, Marcelo (March 14, 2023). "Renzo Gracie vs. Wallid Ismail: The Beginning of Jiu-Jitsu's Greatest Rivalry". Sherdog. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "About Royce | Royce Gracie". 2014-12-13. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Network | Royce Gracie". 2014-12-13. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ "Campeão do primeiro UFC, Royce Gracie difunde jiu-jitsu como defesa pessoal". ge (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ "About Royce". ROTCEGRACIE.tv. September 17, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ Barghouty, Leila (2021-10-05). "Famed MMA fighter's son enlists on an Army Ranger contract". Army Times. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Explains Why He Wears a Blue Belt instead of a Coral Belt". BJJEE.com. 8 September 2021.

- ^ Zidan, Karim (2018-10-24). "Why are MMA fighters endorsing Brazil's far-right presidential candidate?". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ^ "@realroyce on Twitter". Twitter. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ SIG SAUER, Inc (2022-07-05). SIG Hunter Games Closing Ceremonies. Retrieved 2024-09-18 – via YouTube.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (2023-07-06). "ESPN Films Sets Gracie Family Docuseries, Guy Ritchie Among Executive Producers (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 2023-05-26.

- ^ "Royce Gracie: Rener & Ryron Are Misrepresenting Jiu Jitsu". MMA Latest News & Fights Videos l UFC Fighting Videos l Female MMA Champion. Archived from the original on 2014-10-25. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ^ "Royce Gracie Says His Issue with Eddie Bravo is His Drug Use, Not His Jiu-Jitsu or Family Feud". mmaweekly.com. 29 April 2014.

- ^ Gift, Paul (11 January 2016). "IRS goes after Royce Gracie claiming tax underpayment, fraud totaling $1.15 million". Bloody Elbow. SB Nation. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Jones, Phil (30 June 2023). "Royce Gracie Settles Tax Fraud Cases With IRS". Jitsmagazine. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "Royce Gracie | BJJ Heroes". 22 November 2010. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ a b Gerbasi, Thomas (2011-10-17). UFC Encyclopedia - The Definitive Guide to the Ultimate Fighting Championship. New York: DK. p. 148. ISBN 978-0756683610.

- ^ a b Gerbasi, Thomas (2011-10-17). UFC Encyclopedia - The Definitive Guide to the Ultimate Fighting Championship. New York: DK. p. 149. ISBN 978-0756683610.

- ^ a b Gerbasi, Thomas (2011-10-17). UFC Encyclopedia - The Definitive Guide to the Ultimate Fighting Championship. New York: DK. p. 150. ISBN 978-0756683610.

- ^ a b Gerbasi, Thomas (2011-10-17). UFC Encyclopedia - The Definitive Guide to the Ultimate Fighting Championship. New York: DK. p. 151. ISBN 978-0756683610.

- ^ "UFC 45: Revolution". Fighttimes.com. 2003-11-21. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ "By The Numbers - Super Streaks". UFC.com. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 2023-11-20.

- ^ "UFC Fight Night 232 post-event facts: Brendan Allen on an all-time submission streak". MMA Junkie. 19 November 2023. Retrieved 2023-11-20.

- ^ Mike Bohn (2024-09-03). "UFC Fight Night 242 pre-event facts: Ovince Saint Preux can inch closer to Jon Jones' records". mmajunkie.usatoday.com. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Thomas Gerbasi (November 23, 2018). "25 Years - The Submissions - Part 5". Ultimate Fighting Championship.

- ^ "FightMatrix MMA Awards". FightMatrix.com.

- ^ "Black Belt Hall of Fame . Inductee Directory". Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ "Browne, White, Gustafsson, Rousey winners at World MMA Awards VI". fightersonlymag.com. February 8, 2014.

- ^ "Gracie tests positive for off-the-chart measurements of steroids". ESPN.com. 17 July 2007.

External links

[edit]- Royce Gracie at IMDb

- Official website

(Offline)

(Offline) - Professional MMA record for Royce Gracie from Sherdog

- Royce Gracie at UFC

- 1966 births

- Living people

- Brazilian emigrants to the United States

- Brazilian male mixed martial artists

- Brazilian Muay Thai practitioners

- Brazilian people of Scottish descent

- Brazilian sportspeople in doping cases

- Martial artists from Rio de Janeiro (city)

- Sportspeople from Torrance, California

- Welterweight mixed martial artists

- Doping cases in mixed martial arts

- Middleweight mixed martial artists

- Light heavyweight mixed martial artists

- People awarded a coral belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- Gracie family

- Ultimate Fighting Championship male fighters

- Mixed martial artists utilizing Muay Thai

- Mixed martial artists utilizing Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- Brazilian jiu-jitsu practitioners who have competed in MMA (men)

- 20th-century Brazilian sportsmen